The Book of Oghams

In Lebor Ogaim – the Book of Oghams

is a Middle Irish

work which survives in a small number of late mediaeval or early modern

manuscripts. It consists of collections of Bríatharogaim, two

word kennings explaining the meaning of the ogham characters much

in the same way as the lines of the Norwegian and Icelandic rune poems.

The conventional title is supplied by a reference to it in Auraicept

na n-Éces – The Scholars’ Primer

, a related text found in

some of the same manuscripts.

The work ends with a collection

of secret modes of writing ogham, some reminiscent of cryptic runes.

Among these are two younger fuþarks with one set each of rune names and

sound values. The fuþarks are given the titles Gallogam –

foreigner-ogham

and Ogam lochlannach – ogham of the

Scandinavians

. Both of these could also have been translated

idiomatically as Viking ogham

.

The Book of Ballymote

Leabhar Bhaile an Mhóta – the Book of Ballymote, Royal Irish Academy MS. 23 P 12, is a vellum manuscript written at various times and places by different hands. One part is datable to the last years of the 14th century; other parts, including the Book of Oghams, seem to date mainly to the first half of the 15th century.

The fuþarks are here the final entries in the section on cryptic oghams, in difference to the other manuscript where they occur a bit earlier in the same section, and in reversed order. However, the Book of Ballymote has two characters in the corresponding place that turns out to be two runes belonging to its second fuþark. The difference in position and ordering must thus be due to the scribe copying this manuscript wanting to keep the fuþarks from interrupting the material on oghams proper, but not recognising these two characters as part of the runic material.

National Library of Ireland, MS. G 53

This is a fairly late manuscript, dating from the 17th century. With minor differences, it contains the same runic material as the Book of Ballymote, but retains its original placement and ordering. The two fuþarks are consequtive entries, but fall at the bottom of one page and the top of the facing one respectively. The internal layout of the fuþarks and the accompanying material seems on the other hand to be less original here, presumably being modified due to the smaller page width of this manuscript.

Other manuscripts

The Book of Ogham is found in at least three further manuscripts, but as images of these have not been available to me, I cannot place them in the stemma.

British Library Add MS 4783, is a miscellany volume containing among other things as folios 3–7 a 15th century vellum manuscript that includes the Book of Ogham. A description is found in in R. Flower, Catalogue of Irish Manuscripts in the British Museum, 1926, ii, pp. 519-524. Derolez mentiones that this contains the runic material.

Trinity College Dublin, MS 1337, formerly known under the signature H.3.18, is a 15th and 16th century vellum miscellany manuscript with the Book of Ogham on pages 26–35. A description is found in Catalogue of the Irish manuscripts in the Library of Trinity College, Dublin, 1921, pp. 140–142. Images of this has now become available, and this page will in time be reworked taking this into account.

Trinity College Dublin, MS 1295, formerly known as H.2.4, is a 1728 copy of parts of the Book of Ballymote. It contains the Book of Oghams, but as there is no reason to believe that other manuscripts now lost were consulted in making the copy, it has no additional value for the analysis of the contents.

Relationship between the manuscripts

The Book of Ballymote, hereafter referred to as BB and National Library of Ireland, MS. G 53, hereafter G 53 are so similar that they must be assumed to be copies of the same lost manuscript with few or no intermediate copies. Any differences between them must be due to errors or editorial choices in the making of the extant copies, and by weighing the probabilities of different types of change, it is possible to establish a fairly good picture of the state of the source manuscript, hereafter referred to as *Z.

Several features that are shared between the two extant manuscripts are inconsistent with what is known about runes from other sources. As these must have been present in *Z, they are best explained as copying errors not present in a postulated ultimate source manuscript *X. While there is no way to tell how many generations of copies that lies between these two lost manuscripts, it can be assumed to have been at least one. The reason for supposing such an intermediary manuscript *Y is given in the section on sound values below.

| *X | ||

| *Y | ||

| *Z | ||

| BB | G 53 | |

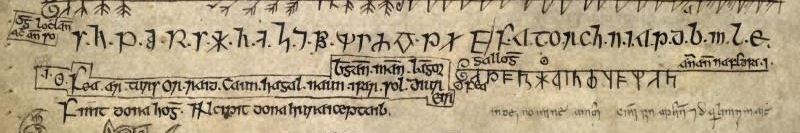

Fuþark 1 – Gallogam

Fourteen of the sixteen runes of the basic fuþark are written

hanging down

from a horizontal line. The remaining two runes,

f and k, are slightly larger and written across a second

horizontal line above this; it is this pair that became separated from

the rest of the runic material in BB. The rune-forms are rather badly

preserved, but as they are close to identical in the two manuscripts,

this must also have been the case in *Z. They are based on short-twig

runes with long-branch h, m and ʀ. Several of the

non-symmetrical runes are reversed, which is quite surprising, as with

the rune-forms used, there are two pairs of runes distinguished solely

by orientation.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

| BB |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| G 53 |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ᚠ | ᚢ | ᚦ | ᚭ | ᚱ | ᚴ | ᚼ | ᚿ | ᛁ | ᛆ | ᛍ | ᛐ | ᛓ | ᛘ | ᛚ | ᛦ | |

| ← | ← | ← | ← | ← |

Rune 1 could be described as a bind-rune combining a normal and a turned f. The top branches are of similar length, while the lower ones are unequal (though the longer one does not reach the edge of the line in G 53). There is no obvious reason why this rune and number 6 should be taken out of the main fuþark line.

2 is reversed, and presumably based on the form similar to an inverted k (which is given as the standard form for short-twig runes in Runica Manuscripta, but which is not the most common form). The shape is similar in both manuscripts; in BB it differs from 15 only in size.

3 is highly influenced by insular letterforms. Particularly in G 53, the bow extends to an unusually large proportion of the line height.

4 In both manuscripts, this rune is indistinguishable from rune 13. These runes have several variant forms, of which most can be used for both values. However, in any given inscription there must be a consistent way to distinguish them; either by falling versus rising twigs, or by left-hand or right-hand placement of one-sided twigs. The least amount of distortion presupposes forms where both runes have one-sided twigs to the right, falling for ą and rising for b.

5 shows the greatest difference between the two manuscripts; both are quite deformed, but still recognisable.

6 is again highly influenced by letterforms, with the branch curving back to the top of the stave, forming a closed loop. At the other end the branch continues across the stave and then curls downwards.

7 is very well preserved in BB, where the only deformity being that the branches are somwhat long in relation to the stave. G 53 is more sloppily drawn, but fully recognisable.

8 is on the other hand badly preserved, but less so in G 53. Here the branch curves back towards the stave, a development that in BB goes further and changes the branch to a closed loop. In the former it is indistinguishable from rune 15.

9 is due to its simple shape well preserved in both manuscripts. In

G 53 this and several other runes have a serif

extending to the

left from the top of the stave; in BB this only occurs on the two runes

placed on a separate line.

10 has different deformations in the two manuscripts. In BB, the branch extends down to the bottom edge of the line, and is slightly curved, whereas in G 53 it is of a more normal size, but much more highly curved. The latter ends up indistinguishable from rune 16.

11 is of a peculiar type. Epigraphically, short-twig s consists solely of the upper half of a stave, sometimes with a dot at the lower end (as always such a dot could also take the form of a short horizontal stroke). In manuscripts, this dot frequently becomes an open circle, which might further grow to fill the lower half of the line, resulting in a full-height rune. BB has this latter type, only with the stave extended to bisect the circle, while in G 53, it continues below the circle as well.

12 is highly unusual. It seems to be a reversed version of a rare type with a small rising twig to the right near the top, distinguished from k solely by the slightly smaller size of this feature. In G 53, it is in addition more strongly slanting than the other runes.

13 is fairly well-preserved, even if the brances are too close to horizontal. In both manuscripts it is indistinguishable from the reversed rune 4.

14 is well-preserved, especially in BB.

15 is very deformed in both manuscripts, being both reversed and having the branch placed too low. It could possibly be an inverted version of the same rare type as mentioned under 12 above, which should have the same shape as that rune has in BB, only with a smaller twig. In BB it is very similar to rune 2, only larger. In G 53 the branch also curves back towards the stave, making a closed loop, resulting in the rune being indistinguishable from rune 8 which shares the latter error.

16 lacks the left-hand branch in both manuscripts, but must clearly originate as a long-branch form. In BB the remaining branch is angular rather than curved.

Three short text fragments and the list of rune names described below is placed in close connection to fuþark 1, though with some differences between the two manuscripts. Their contents are largely the same in both manuscripts, but their placement relative to each other and the main material differ. Presumably, BB is closer to *Z in this respect, but contains marks suggesting that the texts were regarded as belonging in other places. The different layout in G 53 seems to be caused by a rearranging based on an interpretation of corresponding marks in *Z.

In BB, the text fragments are: A) above the left end of the fuþark

line ᵹɑlloᵹ̅ ʘ

; B) below its left end ʘ ꝼeɑ

and C) above its right end ɑn̅ɑn̅ nɑ ꝼƐꝺꞅɑ·ı·

. The (dotless) i with

point on either side is an abbreviation similar to i. e.

. Here,

however, both this and the dotted circle seems to be intended as

reference marks, which are also placed (in that order) in front of the

list of rune names, suggesting that the corresponding text fragments

should be moved to there. As the entire work in question is about ogham

(ogam

in Irish spelling), this term occurs frequently, and is

abbreviated og

with a bar above the g. Even though

am

would be an acceptable expansion of a nasal bar, it must be

considered a general abbreviation bar here, as hoᵹ̅

just below the runic section must be expanded

to the inflected (and lenited) form hogmaib

. Text A thus

unambigously expands to Gallogam

, which makes perfect

sense as the name of this entry in the list of secret oghams.

Gall

generally means just foreigner

, but in the period

predominantly refers to Scandinavians. Text B makes no linquistic sense,

and can hardly be anything but an aborted start of the list of rune

names, and as such redundant. Assuming that the second to last letter is

spurious, text C expands to anmann na feda

meaning

names of the characters

, which makes perfect sense to place in

front of the name list.

In G 53, A and B are run together in front of the fuþark as Ᵹɑ̣ll oᵹ̅ ꝼƐɑ̣

. Disregarding the redundant

fea

, the title is here written in two words: Gall

ogam

. Underdotted a here represents an open-topped

letter variant that cannot be consistently told apart fom u, but

must be identified as a from context. This includes instances

where a reading of a is required for the linguistic meaning, and

where the letter forms the first element of a diphtong where u

would not appear. In the following it is also used without such context

where BB has an unambigous a in the corresponding place. For C,

this manuscript has Ɑ͞nmɑ̣nꝺc̣e nɑ̣ꝼƐꝺꞅo·ı·

. The

bar above the first two letters might suggest a double n

, but is

better regarded as redundant. The possible c

and fairly clear

e

at the end of the first word does not make sense and has no

parallel in BB, and must also be disregarded as spurious. This leaves

the first word as anmand

, a variant of BB’s anmann

with

the same meaning. There is no space after the word na

; in the

following word, the letter e

is unclear, and its final a

is replaced with o

. Finally, even though the text is moved to

where it belongs according to the reference mark, that mark is retained

as if part of the text itself. The density of errors in such a short

text suggests that the copyist did not understand his source text, and

accidentally introduced several misreadings. One should not rule out the

possibility that the BB scribe consciously emended an unclear source

text into something meaningful; but as that reading makes perfect sense

and the alternative does not even form proper words, the principle of

lectio difficilior potior does not apply here. Note that the

presence of a presumably spurious s

as the second to last letter

just as in BB confirms that this was present in *Z.

The rune names

In BB, the first twelve rune names are written on one line to the

left of the fuþark. The names are separated by dots, except that two

consecutive names are erroneously joined into one word. After the

twelfth name, this line reaches the fuþark, and the the list continues

with the next three names above the right-hand end of the

initial line. This parallels the space-saving device used elsewhere in

this and other manuscripts, where the text following the end of the

first line of a new paragraph continues into the gap to the right of the

last line of the previous paragraph before starting a second full line

below the first. Here there is no specific gap to fill, but yet the

extension

to the line starts too far to the right to fit all

names, so the sixteenth and final one is placed alone below the right

end of the initial line. The list is set apart from the surrounding

material by a border following the contours of these lines.

G 53 has a more complex layout, with an irregularity that is most

easily explained by *Z having the same layout as BB (though not

necessarily including the border). The list of names here start above

the middle of the fuþark, immediately following the introductory text

fragments A and B discussed above. It reaches the edge of the page after

just eight names, with the following four placed above the right end of

the line. The first two of the latter are the ones interpreted as a

single word in BB, and are here written without a separating dot between

them, just a slight space. These two lines correspond to the initial

line of BB. The remaining four names are here written pairwise in two

short lines below the right end of the initial line. However, the first

of these lines starts with the sixteenth and last name of the fuþark –

written alone in this position in BB – followed by the first of the

three names of BB’s upper extension line; and then the remaining two on

the second lower extension line. As a result, the last name accidentally

gets promoted

by three places in the ordering.

| BB | G 53 | *X | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Ꝼeɑ | Fea |  |

ꝼeɑ̣ | fea | feu |

| 2 |  |

ɑꞃ | ar |  |

ɑꞃ | ar | ur |

| 3 |  |

ꞇuꞃꞅ | turs |  |

ꞇuᷓꞅ | turs | turs |

| 4 |  |

oꞃ | or |  |

oꝛ | or | os |

| 5 |  |

ꞃɑıꝺ | raid |  |

ꞃɑıꝺ | raid | raid |

| 6 |  |

cɑun | caun |  |

cɑ̣un | caun | caun |

| 7 |  |

hɑᵹɑl | hagal |  |

hɑ̣ᵹɑ̣l | hagal | hagal |

| 8 |  |

nɑun | naun |  |

nɑ̣un[ | naun | naud |

| 9 |  |

ıꞅɑꞃ | isar |  |

ıꞅ | is | is |

| 10 |  |

ɑ̣ꞃ | ar | ar | |||

| 11 |  |

ꞅol | sol |  |

ꞅol | sol | sol |

| 12 |  |

ꝺıuꞃ | diur |  |

ꝺı**[ | di… | diur |

| 13 |  |

b͞ᵹɑ͞n | bergann |  |

b̅ᵹ*[ | berg… | bergan |

| 14 |  |

mɑ̅n | mann |  |

mɑn̅ | mann | mann |

| 15 |  |

lɑ̅ᵹoꝛ | langor |  |

lɑnᵹoꝛ | langor | laugor |

| 16 |  |

eıꞃ | eir |  |

eıꞃ | eir | eir |

Names 1 and 2 both have a

where u

would be expected. In

the first, G 53 has an open-top a

, but in the second an

unambiguous a

. In the remaining names (where a

in all

cases is correct) it has five open-topped and three unambiguous ones; BB

has unambiguous a

in all instances. While the open-topped

a

in the first name in G 53 cannot be used to argue for a reading

of u

in *Z, it sheds light on a specific type of corruption

commonly occurring in the process of copying manuscripts in the insular

script. Copyists would become used to seeing the ambiguous letter-form

where context made it clear that a

was meant, and habitually

correcting it to a clearer form. Occasionally in instances where

u

was correct, but this was not confirmed by context, the copyist

would hypercorrect this to the more frequent letter a

. In this

and similar cases, it is unproblematic to reconstruct forms with

u

in *X based on evidence external to the manuscripts

themselves.

3 is written quite straightforwardly in BB, but abbreviated in G 53.

The abbreviation may at first glance look like two dots above the

u

, but closer inspection reveals it to be a wavy line similar to

a flattened open-topped a

. Due to the angle of the pen, the two

short downward strokes are broad and end up looking like dots, while the

connecting upward stroke is thin enough to be hard to notice. This sign

indicates a following r

, re

, ra

or ar

; here

the first of these corresponds to BB and the rune name as known from

other sources. The initial letter t

is discussed below.

4 is written with different letter variants of r

in the two

manuscripts, whereas an s

would be expected. G 53 has the r

rotunda

which is expected after letters with rounded right edges (as

both manuscripts have in name 15), while BB atypically for this position

has the otherwise more commonly occurring insular r

. As this is

very similar to an insular s, particularly if that was immediately

followed by a dot, it must be assumed that the scribe of *Z miscopied an

insular s in *X as an insular r.

5, 6 and 7 are fairly straightforward. For the use of d

for

Old Norse ð

see below; c

for (normalised) Old Norse

k

is entirely expected.

8 contains an obviuos error, reading naun

rather than the

expected naud

. Here the scribe of *Z must have been guilty of a

dittography, repeating the coda of the preceding similar name

caun

. In G 53 it cannot be ruled out that something is written

after this name, as the right margin is obscured by the following page

in the image.

9 and 10 are written as a single name in BB; in G 53 they are separated by a narrow space, but there too the dot between them is missing. The latter might be a faithful reproduction of *Z, but *X must have had the names written separately.

11 bears no sign of corruption. Final u

is lost in this name

while it is retained in the first.

12 is clear in BB, but in the image of G 53, the right-hand part of

the name is covered by the following page. The visible remains are not

entirely consistent with how it is written in BB, but there is nothing

unexpected about that form. The initial letter d

is discussed

below.

13 is incomplete in the available image of G 53 like the previous

name, but what is visible is consistent with BB. There it is written

with bars over both the first and second pair of letters. In the first

of these, it is not to be interpreted as a nasal bar, but a general mark

of abbreviation. In other places in the same manuscript where context

makes the expansion clear, b

with a bar above represents

ber

, which is just what is expected in this name. In the

latter, it is presumably meant as a nasal bar, but might have been

introduced spuriously by analogy with the following name.

14 is straightforward. BB has a nasal bar above a

while G 53

places it above the n

instead, but this makes no difference to

the expanded form of the name.

15 is erroneously written langor

in both manuscripts; the

n

is abbreviated as a nasal bar in BB but written out in G 53.

This letter must have originated as a misreading for u

.

16 is the most interesting of all the rune names. The unique spelling

eir

suggests that it was originally written down by an Irish

scribe, and is not adapted from material in Anglo-Saxon, where it would

have been written yr

. There is no reason to assume that the Norse

informant pronounced the vowel as anything other than y

,

though.

Like the sixteenth name, the treatment of the dental sounds points

towards an Irish origin of the list, and not an Irish copy of an

Anglo-Saxon original. Old Norse had three dental phonemes, the unvoiced

plosive t

, the voiced plosive d

and a fricative with the

unvoiced allophone þ

and the voiced ð

. Old Irish had both

plosives, while fricatives only occurred as positional allophones or

lenited variants of these. However, in the Middle Irish period, when

this text was composed, the fricatives developed into non-dental

pronunciations. It is therefore not surprising to see t

and

d

for Old Norse þ

and ð

in turs

and

raid

. It is less clear why tiur

(an older form of

týr

) is rendered diur

, though one may speculate that the

choice was motivated by a desire to preserve the distinction between the

initial sounds of this rune and turs

.

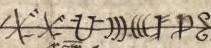

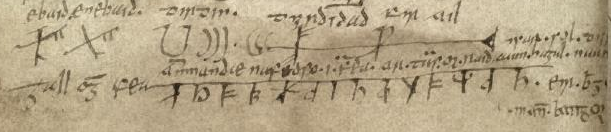

Fuþark 2 – Ogam lochlannach

In the rearranged text of BB, the first line of the runic section

starts with a fuþark with one of the sixteen basic runes accidentally

omitted, and with four supplementary runes. The runes are separated by

dots; though towards the end only sporadically. The strokes are

influenced by how letter are drawn with pen on parchment, resulting in a

pronounced serif pointing to the left from the top of every rune.

Otherwise the shape of the basic runes conform closely to the older

Norwegian

runes with long-branch s. The only grave error is

that the f-rune only has one branch, making it indistinguishable

from the k-rune (both somewhat deformed, ending up similar to an

insular s). Apart from the third one, the additional runes are

quite strange and hard to identify.

Following this on the same line, separated by a slash that looks as a later addition, is a transliteration of the sixteen basic runes. The letters are separated by dots. In G 53, the runes are placed on a line with a feather mark, with the staves and some branches crossing this. The transliteration is here placed on the following line, but as the slash separator is retained at the end of the fuþark, this is likely a change from *Z due to the narrower page.

Squeezed in to the left of the top of this line is the heading oᵹ̅ loċlɑ͞n|ɑċ ɑ͞n ꞅo

(BB), which expands to

ogam lochlannach annso

or

ogham of the Scandinavians here

. G 53 has oᵹ̅

loċlɑ͞nɑċꞅo

which seems to be a corrupt copy of the same.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

| BB |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| G 53 |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ᚠ | ᚢ | ᚦ | ᚮ | ᚱ | ᚴ | ᚼ | ᚿ | [ᛁ] | ᛆ | ᛋ | ᛐ | ᛒ | ᛘ | ᛚ | ᛦ | ᚤ? | ᚵ? | ᛅ | ᚯ? |

Rune 1 is as mentioned the least well preserved, having lost one of its branches, ending up identical to rune 6. As both have gained a downwards turn at the end of the branch as well as the serif on the stave, they end up very similar to an insular s.

In 2 the branch starts lower down than usual. This may indicate that

the ultimate source had the rare inverted k

form given as the

standard form for short-twig runes in Runica Manuscripta.

3 has an oversized loop reaching too high.

4 has branches that curves back towards the stave, making them look more like tiny loops.

5 is quite dissimilar in the two manuscripts, but easily recognisable in both.

6 is almost identical to 1 as described above.

7 has oversized branches.

8 has a branch that is both curved and extends too far down.

9 is missing in both manuscripts.

10 is quite well-formed apart from the serif which is almost as large as the branch.

11 is clearly recognisable as a long-branch s in both manuscripts, though the lower half-stave is curved in G 53.

12 is a bit odd. The stave is a bit curved in BB and slanting in G 53. The branch is horizontal in BB and unusually long in G 53; in both it curves upwards at the end to form a serif.

The loops of 13 are of normal size but separate in BB, while they are connected but of diminutive size in G 53.

14 is well-preserved in both manuscripts.

15 has a curving branch in BB. In G 53 it is also curving, but ascending rather than descending, making the rune indistinguishable from 1 and 6.

16 is well-preserved in both manuscripts, apart from the prolonged stave in G 53.

17 does not look like a rune at all, with its horizontal top and lack of a stave. As the two manuscripts do not differ too much, *Z must have had something similar, but it is not possible to tell how corrupted this copy was. A dotted u-rune is a guess based on what is commonly found in this position, and which rune it is least unlike. This is usually transliterated y, and though it might have different values its presence would indicate that rune 16 has not developed a similar value.

18 is very similar to rune 3, but that does not make much sense as an additional rune. As with the previous, one may guess at dotted k-rune (transliterated g) based on what could be expected and that it is not entirely dissimilar in shape.

19 alone among the four additional runes looks more or less exactly as one would expect; as the long-branch a-rune which in extended fuþarks is transliterated æ.

20 is very different in the two manuscripts. The shape in BB with its three long horizontal branches is quite un-runic. G 53 has only two branches, and the top one is drawn like rising ones in 1 and 6. Though these are only on the right-hand side, one might in the context of the previous rune hazard a guess at the original might have been the long-branch version of rune 4, transliterated ø.

The sound values

Despite being written in close connection to fuþark 2, it is clear that the sound values does not belong to this. That it contains i which is missing from fuþark 2 is of no consequence, as this may easily have become lost later in the transmission, possibly as late as when *Z was copied. That there is nothing corresponding to the four additional runes is a stronger indication; but the deciding factor is that the values are simply the initials from the list of names, which is in turn closely connected to fuþark 1. An interesting parallel to this is the composite alphabet in St. John’s College, Oxford, MS 17. The list contains two obvious errors, and one of them (along with three peculiar values) is shared with the corresponding names. This means that the list was added to a manuscript later than *X, but the second error not shared with the list of names suggests that this corruption happened between that manuscript and *Z. For this reason, an intermediate manuscript *Y must be assumed.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

| BB |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| G 53 |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| f | a | t | o | r | c | h | n | i | a | p | d | b | m | l | e |

Values 1, 5, 7–10 and 13–15 are identical to the transliteration commonly used today, and what was the primary sound values of the runes at the time.

2 is a rather than the expected u. As mentioned in the section about the rune names above, this substitution is common in insular manuscripts due to the use of the ambiguous open-topped a, and also affects the initial letter of the rune name corresponding to this sound value. While it is possible that the same corruption happened independently in the two lists, it would be less likely to occur spontaneously in the list of sound values where the correct a follows just a few letters later. The shared error thus supports the theory that the entire list sound values was added based on the list of names after the latter had become corrupted on this point.

3 and 12 have their values shifted from þ and t to t and d respectively, as discussed under the rune names above. Again, this would have been somewhat unlikely to happen in the exact same way if the lists were independent of each other.

4 is given the value o. This can not be used as an argument that the value had shifted from ą to o in the source fuþark, as the same is the case for other manuscripts which must be assumed to predate this shift. It must rather be due to the transcriber lacking nasal vowels in his native language as well as means to denote them in writing, and thus interpreting the oral–nasal distinction as one of articulatory position. While this value coincides with the initial letter of the corresponding rune value and is thus consistent with the theory of the list of sound values being derived from that, the value is so common that it hardly lends the theory any further weight.

6 is written c rather than k as is used in modern transliteration. This is entirely due to convention, as k was not used at all in Irish, and c represented this sound in all positions (disregarding lenition which could be unmarked in writing). As for value 4, this is consistent with the derivative theory, but is too common to be claimed as evidence for it.

11 is p rather than the expected s. This is an understandable error, as an insular s followed by a dot differs from a p only by a hairline connecting the letter to the dot. As there is no corresponding error in the list of names, it must be assumed that this corruption occurred after the list of sound values was extracted. Being an obvious error most easily explained by postulating insular s as the immediate source, the discrepancy from the list of names does not undermine the theory of this being the source of the list of sound names.

16 has the unusual and unexpected value e, rather than a representation of either ʀ or y. This is the strongest evidence that the sound values are simply deriveved from the initial letters of the rune names, where the sixteenth name is eir. Here ei must be a rendering of the to the scribe foreign sound y; had the list of sound values been written down at the same time as the name list, one would expect ei rather than just e as the value for this rune. Neither the purported sound value nor the rune name can be used to indicate whether or not the actual sound value had changed from ʀ to y at the time they were written down, as this change had no effect on the name.

Tor Gjerdei@old.no