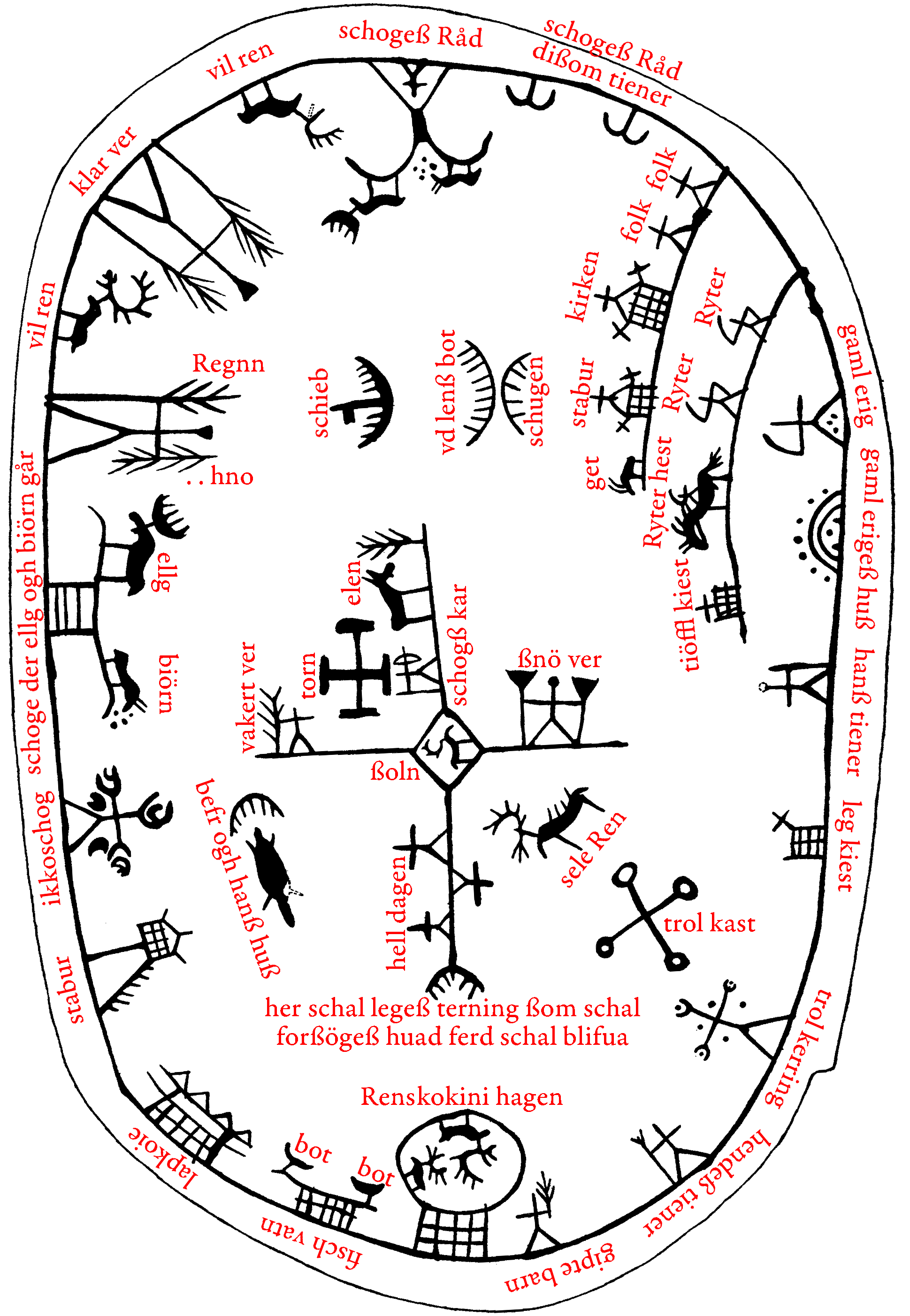

A South Sámi drum, annotated by Olaus Stephani Graan c. 1688

Three unrelated families of Sámi origin with the surname Graan are connected to the documentation of Sámi drums in the seventeenth century. First Johan Graan (c. 1610–1679), the governor of Västerbotten province, acted as a middleman in the collection of the so-called clergy correspondence forming the basis of Schefferus’ Lapponia. Second, Olaus Graan (c. 1620–1689), vicar in Piteå, wrote one of those accounts in 1672. His contribution is in large part a copy of the one by Samuel Rheen from the year before, and seems not to have been used by Schefferus. A namesake of his, sometimes disambigued by a middle name was Olaus Stephani Graan (d. c. 1690), vicar in Lycksele. He was the author of two of the first books to be published in a Sámi language in 1668 and 1669, and is assumed to be the one who annotated a still surviving drum by writing interpretations of its symbols directly on the drumskin.

This assumption is based on an inscription on the drum frame, reading 1688 Den 4 Decemb förährat af F. Chr. Gr. (1688 December 4th donated by F. Chr. Gr.); the donation was to the Royal College of Antiquities in Stockholm. The best match for the abbreviated name seems to be Christoffer Graan (b. 1662), son of Olaus Stephani Graan, even though this does not explain the “F.”. He accompanied a military campaign in Holland in 1688, so he would have had the opportunity to deliver the drum in Stockholm on his way there. Based on the writing style, Ernst Manker finds it more probable that the explanatory text was added by the father than by the son.

What is peculiar about these interpretations is that they reference natural phenomena such as weather where other sources point to mythological meanings, but yet in such a way that they do have some connection. A possible explanation is that the writer knew the deeper meaning of the symbols, but wished to downplay their non-christian religious nature.

Another oddity is that Graan’s native language was Ume Sámi, and he lived and worked in the middle of the Ume Sámi area; yet the drum is of classical South Sámi type both in construction and decoration.

In his monograph, Ernst Manker provides colour and black and white photos of the drum, a tracing of its original design, and transcriptions of the in places quite hard to read explanatory additions. On his tracing, each figure is numbered, and he provides interpretations of his own and those of earlier commentators based on this key. Here I reproduce the colour photo and his tracing; but on the latter, I have removed his numbering and istead added his readings of Graan’s explanations in clearer letters in red. Unusually for a work written in German in the mid twentieth century (at least outside of Switzerland), that monograph is printed with ss for ß. This even extends to the transcription of early modern Scandinavian languages such as here, where the character rather corresponds to modern s than to ss. He also transcribes the letter u/v as v word-initially, but u elsewhere. I have restored the ß’es but retained his distinction in the latter case although it is anachronistic. Based on the photo I have also removed spurious instances of uppercase initials, added or removed spaces between words, and in one instance restored a missing letter.

This method of adding interpretations is unique in that it does not impose any ordering of the individual figures not present in the drum itself. As an English translation of the annotations needs a bit of commentary, it is not feasible to present this in the same way, so I will have to do so in linear fashion here, but keep in mind that the order is essentially arbitrary.

The central rhombus is simply labelled ßoln the

sun

. This is consistent with all other descriptions mentioning it,

but omits that the sun is also considered one of the major deities. No

mention is made of the reindeer drawn inside it.

On the lines extending to left and right from it, there are humaniod

figures carrying identifying attributes, labelled vakert

ver beautiful weather

and ßnö ver snowy

weather

. Frequently, these spots are occupied by the thunder god

Horagalles and the wind god Bieggolmai. Here, the right

one indeed carries Bieggolmai’s characteristic showels, while the

left one more atypically holds what might be a tree or a branch. It is

still certainly meant to be the thunder god, because of the symbol above

him which is identified as torn thunder

(this

word could in other contexts also mean thorn

or tower

, but

the same symbol is found in the same loaction with the meaning

thunder

on several drums).

On the upward extension is a humanoid figure with a bow labelled schogß kar forest man

and an animal looking like a

hornless (i.e. female) elk facing a tree labelled elen

elk

. A male elk with its characteristic horns is frequently seen

in this position on other drums, sometimes a reindeer is found instead

or in addition; one to three humanoid figures without identifying

features are also sometimes seen here. The shape of the humanoid figure

is characteristic of either a Sámi hunter, the archer god

Leibolmai or the goddess Juksakka; more on this below. The

interpretation as a Sámi hunter (possibly the drum’s owner) is less

likely in this area typically reserved for deities.

One the downward extension are three humanoid figures with no

attributes, labelled hell dagen holidays

. The

three Ailekesolmak were gods or angels of the three holy days

(sometimes specified as Friday, Saturday and Sunday, elsewhere as the

Christmas days) and are regularly depicted in this location. At the

lower end of this extension line is an embellishment, and below that the

longest text on the drum: her schal legeß terning ßom schal

forßögeß huad ferd schal blifua here a die will be placed, whose

path will be tried

– the grammar is somewhat tortured here, but

there is no doubt as to the meaning. Read in context of the more

detailed contemporary accounts, this short description confirms that

among the uses of the drum, an important one was to inspect the path of

an indicator moving around as the drum was beaten. It is perhaps not

very important that the term die

is used here, where other

descriptions have a ring, a bunch of rings, a pointer or some other

contraption.

Around the outer edge of the drum is a continuous band with no

defined start or end. Arbitrarily starting at the top and going

clockwise, we first encounter a complex figure labelled schogeß Råd guardian spirit of the forest

. It could

possibly be read as “forest council” instead, but this seems less

likely. Manker’s transcription lacks the final -d here, but not

when it is repeated in the following entry. The figure consists of a

small humanoid figure inside a triangle rising from the baseline, the

top of which extends into two outward-pointing curves. On each of these

curves there is an animal. One is clearly identifiable as a male elk by

its horns. The other has two straight strokes instead of horns, shorter

legs and a group of dots in front of its head. The latter feature in

often used to denote bears and possibly also wolves in other drums; on

this drum an identical figure on the left edge is explicitly ideintified

as a bear. Presumably, the figure is intended to represent

Radien, the highest god. This deity is frequently found in this

position on similar drums, although more commonly denoted by an abstract

house-like structure. This interpretation is supported by the next two

figures — both consisting of a vertical stroke branching into two

outwart-pinting curves, echoing the top of the first figure — being

collectively described as schogeß Råd dißom tiener

these serve the guardian spirit of the forest

.

The next five symbols are not placed on the outer band itself, but on

a curved line branching off it. They are labelled get

goat

, stabur storehouse (for food; on pillars

to keep rodents out)

, kirken the church

and

folk people

(twice). Such a band representing

the settlements of the christian sedentary inhabitants of Norway or

Sweden (or the journey there) is found on many drums, and collectively

called ristbalges the christians’ road

. The

interpretations of the individual symbols seem reasonable. The first of

these indeed seems to depict a goat, as it is drawn with two slightly

curving horns. The next two look like houses with crosses at the roof

ridge and the eaves. As this is the case for the storehouse as well as

the church, it is highly unlikely that the crosses have any specifically

christian significance; the only distinction between the buildings is

their sizes. The two figures individually labelled people

are

drawn as humanoids with no distinguishing features.

Following this is a similar band with four figures, labelled tiöffl kiest devil chest

or devil coffin

, Ryter hest rider, horse

and Ryter

rider

(twice). As a distinct group, this feature is rarer than

ristbalges, but is referred to as Jabmikuči-balges the

road to the land of the dead

in other old descriptions. It is hard

to pinpoint exactly what is meant by the term devil chest

or what

the underlying significance is. The for this interpretation

uncharacteristically religious reference probably means that it is

trustworthy, but this is of little help in understanding it. The close

parallel to another figure labelled corpse chest

, i. e.

coffin

suggests that it is some form of a human grave, as does

its context as part of the land of the dead

. Next to this is a

rider on a horse, which frequently occurs as a representation of

Rota, the demon of disease. The two humanoid figures behind the

horse are connected to this by being denoted riders

despite being

on foot, and by carrying similar curved items in the left hand. In

context, this presumably means that they are servants of

Rota.

Continuing on the outer line, partially underneath the curved branch

of the Jabmikuči-balges comes gaml erig

Satan

, gaml erigeß huß Satan’s house

and

hanß tiener his servant

. The figure labelled

Satan

is drawn with the same attribute as Rota and his

servants in his left hand, but is drawn larger and with a group of dots

between his legs. Everything is consistent with this really representing

the ruler of the underworld, just interpreted as the christian

counterpart. Similarly, the double arc with dots inside and outside

makes sense as some form of dwelling associated with him. Whether or not

the next humanoid figure was originally meant to be his servant is

harder to tell. It is not in any way unreasonable that such a servant

should be depicted, but he is not immediately adjacent, is only

slightly smaller, does not share any characteristic features and is

largely outside the arc of the Jabmikuči-balges. However, no

other interpretation is evident from parallels. The next figure

continues the theme of death, being the leg kiest

coffin

(literally corpse chest

) mentioned above.

The next group consists of three humanoid figures and a symbol above

and possibly related to the first of them. They are labelled trol kerring sorceress

(with trol

kast approximately thrown sorcery

above), hendeß

tiener her servant

and gipte barn where the

exact meaning is uncertain, approximately marriage child

. In this

location, we usually find the three sisters Sarakka,

Juksakka and Uksakka; sometimes also their mother

Maderakka. These mother goddesses were closely connected to

conception, pregnancy and birth, but also to the protection of the home.

When present on a drum, the three sisters tend to be depicted together

and in similar size and style. Usually they are distinguished by

Juksakka carrying a bow, and Uksakka holding a staff with

a forked top in one hand or both, while Sarakka is not identified

by specific iconography. The middle of the figures on this drum is

clearly meant to be Uksakka, but just assuming the two others are

her sisters has its problems not only in the iconography itself, but

also with respect to the labelling. The figure described as a

sorceress

is drawn larger and stylistically different from the

other two, and the second is marked as her servant

which is

consistent with the size difference. On the other hand, the

identification as sorceress

is unparallelled in other

descriptions, and seems to be motivated by the proximity to the cross

with circular terminals above. This symbol occurs on many drums, and

given similar interpretations elsewhere; however, it is normally found

somewhat closer to the central sun cross, and not closely associated

with an agent sending it out. If this figure instead is meant to be

Maderakka or some unidentified and unrelated being, there seems

to be one sister missing. A possible explanation could be that she has

been placed on the line extending upward from the sun instead, as the

humanoid figure there looks exactly like Juksakka would be

expected to look given how Uksakka is drawn. The reason for such

a displacement can be found in that Juksakka is also a hunting

goddess, and thus less limited to home and hearth than her sisters.

Connected to the bottom edge by a gridded structure is a circle with

two reindeer inside, labelled Renskokini hagen, with

unclear word separation. With some leeway depending on how the first

part is broken up in separate words, the meaning is [the] reindeer

herd in[side] the corral

. Such a figure with this meaning is often

found in this location, though normally not connected to the outer

band.

The following two figures are also connected to the outer band with

similar gridded structures. The first is given the overall label fisch vatn fish[ing] lake

, while each of the

structures at the ends is identified as a bot

boat

. Figures representing hunting and fishing are found in this

quadrant on many drums, though not always connected to the outer band.

The second figure is labelled lapkoie Sámi hut

.

Despite the term being singular, the figure seems to depict a camp of at

least four huts. Such figures, though normally consisting of just one

hut or two, is found in this area on many drums.

The same is the case for the next figure, depicting the typical Sámi storage house njalla, elevated atop a tree trunk cut off high enough to make it inaccessible to wild animals who otherwise could get at the food inside. It is labelled stabur just like the storehouse of the farmers described above.

For the remaining figures, it is generally less certain what the

underlying meaning is, despite many having parallels on other drums. The

first one is especially peculiar. It is similar to the uncertainly

identified figure labelled sorceress

on the opposite edge, and as

as some drums have a figure carrying a drum in this area, one could

speculate that it represents a noaidi or the person using the

drum. In sharp contrast to that, the figure is labelled ikkoschog presumably forest with squirrels

. While

it is not easy to see how the figure could represent that, it is worth

noting that another drum indeed has a figure with the same

interpretation in the same area, which clearly depicts a tree with a

small animal climbing it. Some additional support for a wildlife-related

meaning is the proximity to the figure above it, labelled befr ogh hanß huß beaver and its house

, which is

consistent both with its shape and parallels on other drums.

On the leftmost edge is a figure consisting of a sinous line, the

center of which is connected to the outer band by a ladder-like

structure, and on which two animals stand. The animals are very similar

to the ones on the figure at the top, and here they are explicitly

identified as ellg elk

and biörn bear

. It is worth noticing that the term used

for the horned (male) elk here is different from the one used for the

hornless (female) one on the central symbol complex. The two terms were

not used to distinguish between male and female animals, though, and is

rather surprising to find used together. Variants of elg is most

common in Swedish and Norwegian, while elend, elen or

elsdjur might indicate influence from Danish or German. The

entire composite figure is labelled schoge der ellg ogh

biörn går forest where elk and bear roam

. In the context of

the preceeding figures, this might sound reasonable, but the form of the

figure rather suggests a sacrificial bench or possibly a

passevara or sacred mountain

.

Completing the outer band are two humanoid figures, each followed by

a reindeer. The first figure holds a tree-like object in each hand, one

with upward-sloping branches labelled Regnn rain

and the other with downward-sloping brances labelled …hno, presumably snow

. The other figure is similar,

but here the branches are upward-sloping on both sides, and the entire

figure is labelled klar ver clear weather

. As

several figures known from other sources to represent deities are

labelled as weather phenomena on this drum, and these are the largest of

all its humanoid figures, it is tempting to assume that these too

represent deities, although no specific identification of them can be

made.

Both of the reindeer mentioned above are labelled vil

ren wild reindeer

. It is not clear what they represent, but

their labels contrast them with the herd of domesticated reindeer at the

bottom, the unlabeled reindeer inside the central sun symbol and finally

with the free-floating reindeer figure to the lower right of this,

labelled sele Ren harness reindeer

. In the same

area as the latter, similar drums often have a reindeer pulling an

akkja (sledge), supporting the identification made here.

This leaves only the figures floating above the central sun figure

complex. The first of these is labelled schieb

ship

, and a ship is usually found in this region of drums of this

type. What it represents is not clear. The remaining two figures seem to

belong together and are labelled vd lenß bot foreign

boat

and schugen the shadow

(obviously in

the now obsolete sense the mirror-image

). These seem to be

identified mainly by the proximity to the ship, and might well represent

something entirely different, though no alternative interpretation is

apparent.